Welcome to Jackson Hole Week, a thrilling annual event that draws some of the brightest minds in economics right to my doorstep here in Jackson Hole, Wyoming! This annual gathering, proudly sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, is not just any conference; it’s perhaps the most anticipated economic summit of the year.

As the discussions unfold, you can bet that the term “inflation” will echo through the halls, resurfacing hundreds of times. After all, inflation isn’t just a passing topic—it’s considered the most critical economic challenge of our era. But inflation means different things to different people, and its usage has changed drastically over time.

According to my Oxford English Dictionary (the OED, dated 2002), “inflation” is defined as:

(Unduly) great expansion or increase; spec. (a) economics (undue) increase in the quantity of money circulating, in relation to the goods available for purchase; (b) popularly inordinate general rise in prices leading to a fall in the value of money.

The first definition (a) is close to the one I prefer: an “undue” increase in the quantity of money. However, notice that this is much different from the second popular definition—an “inordinate general rise in prices”—which is closer to the definition most economists use today.

In recent years, economists at the Fed and other central banks have adopted the popular definition and narrowed it even further. They now say inflation is an increase, not in “general prices” but in “consumer prices,” as measured by their official price index. So, for example, “inflation” to the Fed doesn’t include a rise in the prices of homes or stocks, but does include a rise in the prices of eggs and cars. The Fed defines inflation as changes in the Personal Consumption Expenditures” index (PCE), which is similar to the well-known Consumer Price Index (CPI). For example, if the PCE increases year-over-year by four percent, the Fed will declare that “the inflation rate is four percent” or just “inflation is four percent.”

Moreover, the Fed now says a PCE rise of over or under 2% per year is undesirable, while an increase of 2% is just right. So, consumer price inflation of 2% is good, they say, while rates higher or lower than that are not good. Their current PCE measure is about 2.6%, so inflation is, by their definition, still too high.

The Purpose of Definitions

But is this definition truly helpful for understanding inflation? Does it help us grasp what it’s like to live in an “inflationary” economy? Does labeling inflation simply as price increases clarify our understanding of those price hikes? In simpler terms, does defining inflation as an “increase in consumer prices” have any real cognitive value? As philosopher Ayn Rand put it, “The purpose of a definition is to distinguish a concept from all other concepts and thus keep its units differentiated from all other existents.”

“Differentiation” requires identifying the essential or most fundamental characteristics of the concept we are considering, because this fundamental characteristic makes the concept different from all others. To take a classic example, we define “man” as the “rational animal” because our rational faculty fundamentally differentiates human beings from all other animals. If we said, “Man is the mammal with an opposing thumb and forefinger,” that might be true, but it would tell us practically nothing about the essential difference between a human and an ape.

To illustrate the problem further, what would you think of a doctor who, noticing his patient has a high body temperature, immediately diagnoses “fever” and plunges the patient into an ice bath? He would lower the patient’s body temperature all right, but also might kill him in the process. Defining the patient’s illness as an increased body temperature obscures understanding of the problem. Any doctor who treated a sick patient this way would be rejected as a quack, as he is assuming a mere symptom is a fundamental problem.

Instead, we’d expect our doctor to go beyond taking the patient’s temperature. He would conduct a battery of tests and notice all other relevant symptoms the tests reveal. Relying on his knowledge and experience, he would find the common denominator, the cause, of all the symptoms he observes. Perhaps he would diagnose dehydration, a bacterial infection, a virus, or a cancer. These underlying causes would determine how he defines the disease, rather than dismissing it as a “fever.”

In the same way, if we define inflation simply as “an unwanted increase in consumer prices,” then anything that increases consumer prices must be a cause of inflation. We then lose the ability to differentiate between price increases caused by an increase in the quantity of money, by a decrease in the quantity of goods sold, or by a change in consumer preferences. For instance, one could claim that price increases due to hurricanes or earthquakes, which cause temporary shortages of goods and raise prices in the short term, are an example of “inflation,” and therefore in the same category as price increases caused by a flood of new money. Obviously, the two are very different. Should both be called “inflation”?

This kind of muddy definition provides cover for politicians and economists to blame inflation on supply chain disruptions related to the COVID pandemic, or on energy shortages caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, or on tariffs. This is convenient, because if they can blame the price increases on some external event, they can disavow responsibility for it. They can also more easily justify rationing or price controls under the guise of “fighting inflation,” as if it is some kind of externally-imposed disaster instead of something of their own making.

Consider this analysis by an economist from a prestigious investment bank, Morgan Stanley, who literally blamed “inflation” on a cyclical weather pattern. The headline reads, “A Headwind for Policy Normalization: Morgan Stanley Adds El Nino to List Of Inflation Risks.” The article then stated, “El Nino most directly affects consumer inflation as food and energy commodities prices pass through.”[i] Morgan Stanley feels this is valid because they define inflation as increased consumer prices. Bad weather can temporarily raise the prices of consumer goods, so an El Nino must be inflationary!

Many years ago, Ludwig von Mises deplored this “dangerous semantic confusion”:

There is nowadays a very reprehensible, even dangerous, semantic confusion that makes it extremely difficult for the non-expert to grasp the true state of affairs. Inflation, as this term was always used everywhere and especially in this country, means increasing the quantity of money and bank notes in circulation and the quantity of bank deposits subject to check. But people today use the term “inflation” to refer to the phenomenon that is an inevitable consequence of inflation, that is the tendency of all prices and wage rates to rise. The result of this deplorable confusion is that there is no term left to signify the cause of this rise in prices and wages … . Those who pretend to fight inflation are in fact only fighting what is the inevitable consequence of inflation, rising prices. Their ventures are doomed to failure because they do not attack the root of the evil.[ii]

If it’s misleading to define inflation as an increase in consumer prices, what is a good definition? The OED says it is an “undue” increase in the quantity of money, which implies “unnecessary” or “unjust.” But how do we determine what is “undue”?

In our Chapter Four of my book, A Black Hole in Economics, I discuss the fact that money creation in a free market is self-limiting due to natural market forces. Commercial banks operating in a free market cannot create an “undue” amount of money, at least not for a prolonged period, because any tendency toward excessive expansion is limited by gold reserves and will self-correct.

If banks operating in a free market cannot create excessive money, we are left with the fact that only government intervention in the banking system can enable a prolonged or persistent increase in the quantity of money. This fact leads us to a better, more useful definition of inflation, developed by George Reisman in his great work Capitalism.

“Inflation itself is not rising prices, but an unduly large increase in the quantity of money, caused, almost invariably, by the government. In fact, a good definition of inflation is: an increase in the quantity of money caused by the government. A virtually equivalent definition is an increase in the quantity of money in excess of the rate at which a gold or silver money would increase.”[iii]

This is the most fundamental definition of inflation I know of, with all credit to Professor Reisman. I also use the term “unproductive money creation,” which I believe is roughly equivalent to “money creation caused by the government.” I say this because there can, of course, be individual instances of unproductive money creation (i.e., bad loans) in a free market, but bad loans cannot be a lasting or systematic characteristic of free-market banking because of its self-correcting nature.

In addition to unwanted price increases, there are other important consequences of excessive money creation caused by the government, which we are about to explore with a famous historical example. The purpose of this excursion into financial history will be to spotlight some of the many malignant consequences of inflation. In reviewing this history, we’ll be like the good doctor who notices his patient has a temperature but delves deeper and discovers many adverse effects arising from a fundamental cause. Some of these effects are unseen at first, and some of them are even more destructive than rising consumer prices, but all of them arise from unproductive money creation caused by the government’s policies or actions.

To appreciate the damage that government money-creation decisions can do, let’s examine a famous modern example of an asset bubble that caused incalculable damage over an extended period. As we dive in, recall the Cantillon Effect, which tells us that prices will go up first at the point where new money is spent. If the new money is spent first on investments, like commercial real estate or stocks, these prices will rise first. If the new money is spent first on consumer items like airline tickets or refrigerators, consumer prices will rise first.

The 1980s Japanese Asset Bubble

As a leading example of bad money creation –properly known as “inflation” – let’s review the Japanese property and stock market bubble of the 1980s, examining both its causes and effects.

Source: tradingeconomics.com

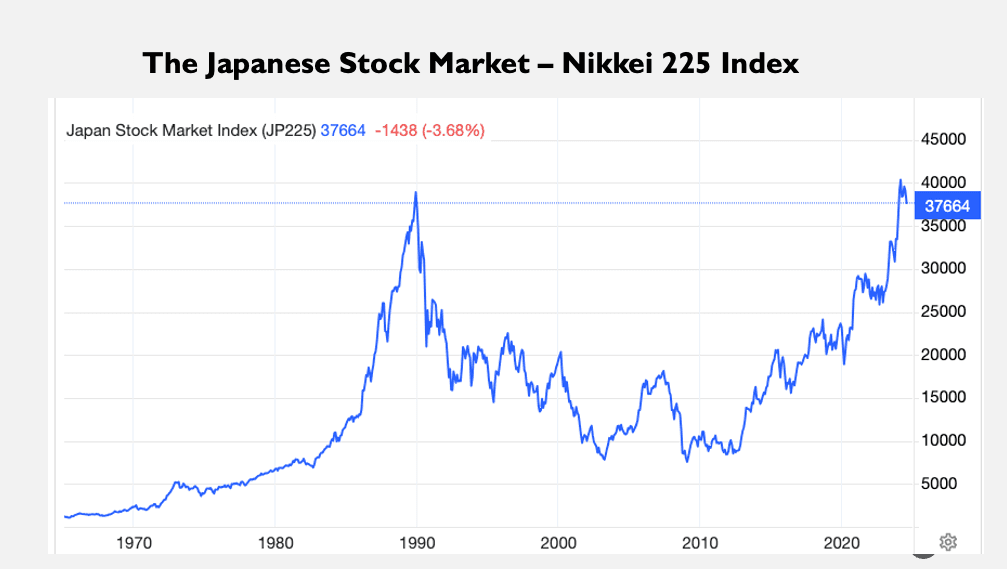

This chart displays the price index of the 225 largest stocks in the Japanese stock market. You’ll notice that Japanese stock prices skyrocketed in the mid-1980s, reaching their peak in late 1989. Following that peak, the market experienced a sharp crash. It took nearly 35 years, until 2024, for Japanese stocks to return to their 1989 price levels. Financial historians regard this episode as one of the most significant asset bubbles in financial history. To explain this notable bubble, I will primarily reference the work of Professor Richard Werner, an esteemed economist from Oxford.

First, a little background on Richard Werner. Werner is a remarkable scholar who speaks and writes fluently in German, English, and Japanese. Prior to and during the Japanese bubble, he was an investment analyst covering the Japanese market for the investment firm Jardine Fleming. In the early 1990s, he conducted research inside the Bank of Japan. In 2003, he published an explanation of the Japanese financial bubble, Princes of the Yen. Fourteen years after the stock market crash, Japan was still reeling from its devastating effects, but no one seemed to understand what had happened. Princes provided the explanation, becoming a Japanese national best-seller, for a while outselling even Harry Potter. There is also a video version of Princes, available online, which I highly recommend, and which is a major source in the account that follows.

We start the story with some basics on the structure of Japan’s financial industry. Following World War II, Japan’s financial regulations and monetary policy were governed by the same system that had run its wartime economy. Japan’s Ministry of Finance (MOF), roughly equivalent to the U.S. Treasury Department, oversaw fiscal matters, while the Bank of Japan (BOJ), the central bank, took care of monetary policy. Under the law at the time, the BOJ answered to the MOF for most policy matters, including interest rate targets. MOF engaged in a fair amount of central economic planning by developing an industrial policy. This was different from financial governance in the Western nations, which did not officially engage in central economic planning.

Within just a few decades after the war, Japan staged an amazing economic recovery. The BOJ played a key role in the initial recovery by creating enough new cash reserves to buy out the banks’ holdings of worthless war bonds, putting the banks on a solid financial footing. The BOJ created these new reserves like all central banks in the post-gold era: it conjured cash reserves out of thin air and used them to purchase bankrupt bonds or bad loans at face value, thus neutralizing and monetizing this debt.

The basic pre-war financial system was still intact but with an important difference: Japan’s system of allocating bank lending to favored industries, which had built a war-fighting machine capable of projecting power around the world, was redirected to a peacetime footing. During the decades following the war, the BOJ continued its wartime policy of allocating credit to its subsidiary banks, a system known as “window guidance.” Under this system, the BOJ gave its member banks quotas for lending, dictating (or strongly encouraging) how much each bank could lend and which economic sectors (steel, autos, chemicals, etc.) should receive the new money. There was some room for flexibility, but the BOJ fundamentally controlled where the new money flowed, especially at the industry sector level.

This was the war economy system adapted to the production of consumer goods for export and domestic consumption. A 1951 amnesty on war criminals returned most of the banking bureaucracy to their previous positions, so the system retained its technical banking expertise. Simply put, the Japanese wartime “money factory” (the commercial banks) converted from financing tanks and submarines to financing factories for peacetime goods.

Japan flourished under this system during the 1950s, 1960s, and most of the 1970s, and its citizens’ quality of life improved rapidly. For example, in 1959 alone, Japan’s real economy expanded by 17%, an almost unheard-of rate of growth, unprecedented (as far as I know) in modern economies. While impressive, this growth was not wholly unexpected for a productive, enterprising population rebuilding an economy that had been utterly ruined by war.

The rate of money creation under this post-war system was fairly high but not extraordinary, typically seven to ten percent per year, according to BOJ statistics available from the US Federal Reserve. However, this rate of money production resulted in only moderate consumer price increases at first because Japan grew its production so fast. For the most part, the production of industrial and consumer goods kept up with the production of money, so price increases of industrial and consumer goods were modest.[v]

However, when the US abandoned the gold standard in 1971, the dollar fell hard against the yen and other currencies, making Japan’s exports less competitive in price. To protect its export markets, the BOJ wanted to weaken the yen. Using its “directed lending” architecture, the MOF and BOJ began aggressively expanding bank lending in the early 1970s, causing annual money supply growth that sometimes exceeded 25% per year.

The resulting devaluation and inflation caused a jump in the stock market. In the 18 months following August 1971, when Nixon announced the abandonment of gold, Japan’s stock market more than doubled. Therefore, I identify the early 1970s as the birth of the asset bubble that eventually blew up in the following decade.

In the 1980s, the world’s central banks, led by the U.S., called for reform. The Americans argued that the Japanese banking system was subsidizing Japanese export industries to the detriment of US companies. In Princes, Werner documents the international pressure, especially from the USA, to abolish the war economy banking system and adopt US-type policies. These recommended reforms included a more Western-style, independent central bank structure. The BOJ agreed with this position and was eager to assert its independence from the Ministry of Finance. But the tradition-minded MOF disagreed, making change very difficult politically.

According to Werner, the BOJ leaders concluded that real change could only occur in the wake of a financial crisis. So, the BOJ set about engineering one, believing that was the only way to convince citizens and interest groups of the need for structural change in the government and the economy.

Werner’s interpretation of the BOJ’s motive is somewhat provocative, but what is not controversial is that in the 1980s, the BOJ started aggressively increasing window guidance toward the real estate sector. Average annual growth in loan quotas grew to 15% by the late 1980s, exceeding what even the bankers asked for. As Richard Cantillon would have predicted, the result was a big boom in real estate and stock market prices.

Look back at the stock market chart to see the parabolic rise of stock prices from 1984 to late 1989. Real estate price increases were even more extreme. Quoting from the Princes video:

“Between 1985 and 1989, stock prices rose by 240%. Land prices increased 245%. By the end of the 80s, the garden around the imperial palace in Tokyo was valued equally to the entire state of California. The market value of only one of Tokyo’s 23 districts, the central Chiyoda Ward, exceeded the value of the whole of Canada. Although Japan has less than 4% of the land area of the USA, its land was valued at four times that of the US.”

By the late 1980s, speculative fervor took over. Traditional manufacturers started playing the markets—these were company hedge funds (the “Zai Tech”) using borrowed money to make speculative investments. Sometimes, their investment gains exceeded the profits from their regular business, as in the case of the car maker Nissan.

Shiny new buildings rose in the cities. The labor market boomed so much that there was worry about a serious labor shortage. Companies enticed new workers by giving them lavish vacations. According to interviews, corporate life became a continual holiday.

Media articles on the “new Japanese economy” famously (and incorrectly) identified the cause of the apparent prosperity as high and rising productivity. Books on Japanese management techniques based on ancient Samurai war strategies were best sellers. As often happens, market observers were confusing brains with a bull market.

Still, the BOJ increased window guidance to property every year. The only way to fulfill these expanded lending quotas was to increase unproductive lending. BOJ offered bankers more than they wanted to lend against property and stocks, and eventually forced the banks to increase their loans. According to an interview with one banker, “A side effect of increased window guidance loan increases was that the banks increased lending even when there was no loan demand.” The BOJ was force-feeding its banks like a farmer feeds a barnyard goose.

Quoting again from the Princes documentary:

“Like all bubbles, the Japanese bubble was simply fueled by the rapid creation of new money in the banking system … . When [Toshiko Fukui, head of the Banking Department at the Bank of Japan] was asked by a journalist, “Borrowing is expanding fast, don’t you have any intention of closing the tap on bank loans?” he replied “Because the consistent policy of monetary easing continues, quantity control of bank loans would imply a self-contradiction. Therefore, we do not intend to implement quantitative tightening.”

From 1987 onwards, it was not borrowers seeking loans, but bankers pursuing potential customers. Anecdotes from this period abound. Young people in their 20s on modest salaries were given loans for second and third homes. Bankers pursued clients like street peddlers. According to one interviewee: “If a newlywed couple wanted to buy a house, banks would offer double the amount they asked for.” To push the loans, bankers made increasingly exaggerated assessments of land value, which made the loan-to-value ratios look better.

The average Japanese citizen knew something was wrong. People in the street called it “excess money.” From the Princes documentary:

“Only economists, analysts, and those working in the financial markets or for real estate firms knew better. They dismissed such simplistic analysis. Land prices were going up for far more complicated reasons than just excess money, they claimed. Ordinary people simply did not understand the intricacies of advanced financial technology.”

The bubble eventually spilled over into international investments as wealthy Japanese took their money abroad. Japanese collectors dominated the art world in the 1980s. Japanese tycoons made high-profile purchases, like The Rockefeller Center, Columbia Pictures, and Pebble Beach Golf Course. Hawaii real estate soared due to Japanese demand. In 1986, Japanese money bought a staggering 75% of all new US treasury bonds sold at auction.[vi]

Importantly, it was not only the absolute level of money growth that caused the bubble, but the direction of spending of the new money that was supplied, first to the real estate sector and then to stock investors, but not towards firms that invested in the production of consumer goods.

Recall the three-hundred-year-old wisdom of the Irish-French economist Richard Cantillon. Cantillon’s important contribution to understanding inflation was the insight that an increase in money’s quantity does raise prices, but not all prices at the same time or to the same extent. He expressed this principle with a creative analogy:

The river, which runs and winds about in its bed, will not flow with double the speed when the amount of water is doubled.[1]

If new money is spent and continually re-spent in the commercial property universe—that is, if the proceeds from property sales are reinvested in other properties—it might take years for this money to “escape” to be spent on non-property commodities. Under these conditions, it’s clear that property prices must rise right along with the quantity of new money.

A similar thing happened in the USA during the early 2000s housing boom. The process consists of lending (injecting new money) into an asset class that is rising in price because of previous injections of new money. It was the same process that fueled the mortgage lending and house price booms in the United States and the United Kingdom in the 1980s.

The stock market boom in the 1920s had developed the same way. In the United States, banks loaned against stocks as collateral. Stock investors usually buy stocks, and that is what they did with their new money. As each bank took the stock price as a valid collateral value, it created new money to buy more stocks. As more money entered the stock market, the owners of stocks continued to borrow and buy more, causing stock prices to rise. Lather, rinse, repeat. The principle remains the same in all asset bubbles.

It’s been said that easy money is a virus that turns investors’ brains to mush. In Japan, as in most financial bubbles, in the latter stages, widespread misunderstanding contributed to the continued unwarranted expansion of money. According to Werner, “Each bank thought it was safe to accept a certain percentage of the value of the stock as collateral, but it was the actions of all banks together that drove up the overall market.”

The Japanese asset bubble continued inflating right through the late 1980s. Viewed over the long term, the inflation in the value of Japanese real estate was staggering. According to Werner, “In Japan, total private sector land values rose from 14.2 trillion yen in 1969 to 2000 Trillion yen in 1989.” This is an increase in prices of 140 times in 20 years, which equates to a rate of increase of about 28% per year.

Then suddenly, in late 1989, the party stopped. At his press conference as the 26th governor of the Bank of Japan, Yasushi Mieno said, “Since the present policy of monetary easing had caused the land price rise problems, real estate lending would now be restricted.” From the video:

“He looked around, looked at the bubble, asset prices rising, the gap between rich and poor getting bigger. Let’s stop it. His name was Mr. Mieno and he was a hero in the press because he fought against this silly monetary policy. But the fact was, he was deputy governor during the bubble era, and he was in charge of creating the bubble.”

Almost overnight, land and other asset prices stopped rising. In 1990 alone, the stock market dropped by 32%. Then, in July 1991, window guidance was abolished. Bankers were now left almost helpless because they did not know how to make their lending plans anymore. Without window guidance, they had no idea how much to lend, or to whom. As banks began to realize that the majority of the JPY 99 trillion in bubble loans was likely to turn sour, they became so fearful that they not only stopped lending to speculators but also restricted loans to anyone else, even those deserving of credit.

Without new money to feed its rise, the stock market continued to collapse, and with it many of Japan’s highly indebted companies. Many listed companies went under. Between 1990 and 2003, 212,000 companies went bankrupt. In the same period, the stock market dropped by 80%. Land prices in major cities fell by up to 84%. Five million Japanese lost their jobs and did not find employment for years. Suicide became the leading cause of death for men between the ages of 20 and 44. According to anecdotal reports, people were hanging themselves and going missing on a daily basis.

But BOJ Governor Mieno found a silver lining in the catastrophe, saying it made the population conscious of the need to implement economic transformation, by which he meant central bank independence. By Werner’s detailed forensic account, Yasushi Mieno had created the bubble, and Yasushi Mieno popped the bubble.

In the years following the bust, several recovery remedies were tried. The MOF pressured the BOJ to lower interest rates to spur lending, but that didn’t work even when rates were pushed to near zero. With no appetite among businesses to borrow, the BOJ was pushing on a string.

Next, the MOF tried to devalue the yen versus the dollar to stimulate exports. But the BOJ sold assets to raise yen to buy dollars, decreasing the quantity of money in the economy, which was deflationary in an already deflating economy. So, despite the BOJ’s intervention in the currency market, the yen did not weaken.

Then, the MOF tried fiscal stimulus, which was supposed to increase loan demand. But they were funding government spending through taxation. With no increase in the money supply, the asset price implosion continued.

By Werner’s account, the BOJ refused to engage in the necessary money creation that would alleviate the crisis, deliberately prolonging the recovery just to get the structural changes they wanted. Finally, in 1998, the Princes of The Yen at the BOJ got their wish and became independent of the MOF. But this had come at great cost to the Japanese people.

Werner sums up the boom-and-bust pattern as follows:

Asset inflation can go on for several years without major observable problems. However, as soon as the credit creation for non-GDP transactions stops or even slows, it is ‘game over’ for the asset bubble: asset prices will not rise any further. The first speculators, requiring rising asset prices, go bankrupt, and banks are left with non-performing loans. As a result, they will tend to reduce lending against such asset collateral further, resulting in further drops in asset prices, which in turn create more bankruptcies.

What conclusion can we draw from the famous Japanese asset bubble? As Werner puts it, “central banks hold obscure, independent powers that are not always well understood.” But we do know their main weapon is the power to cause the banks to create new money and distribute that money to specific recipients who spend the new money in specific markets.

To conclude on the 1980s Japan financial bubble: For years, new money was knowingly directed by a central monetary authority into property markets. This caused a large and rapid increase in property prices that spilled over into the stock market, international investment, speculation, and gambling. The consequences of this misdirected credit were many years of distorted price signals, malinvestment, and wasted capital.

When credit creation was withdrawn, the bubble burst, followed by years of deflation, stagnation, and severe economic and social hardship, not to mention widespread poverty and suicide.

In such situations, the best option, in my view, is to let markets repair the economic damage through free market price discovery and creative destruction. But the truth is, once a credit bubble has been created, there are no painless recovery options.

The Lesson Restated

Japan’s asset bubble serves as a great learning example because it has all the key elements found in modern asset bubbles. First, banks create excessive amounts of money under the direction of a central monetary authority. Then, this new money flows into buying assets, driving up their prices. Higher asset prices increase the value of collateral, leading to more borrowing and further money creation, which pushes prices even higher. As a result, asset owners get richer while the less fortunate are left behind.

As the bubble continues to grow, monetary authorities feel confident about their actions, mistakenly believing that inflation isn’t a concern since consumer prices are only rising moderately. This money pumping persists for years, creating a speculative frenzy that ensnares many unsuspecting individuals, ultimately causing harm to millions of lives.

Let’s conclude with a couple of summary points.

First, a correct definition of inflation—an increase in the quantity of money caused by the government—helps us identify all the adverse effects of unproductive money creation, not just unwanted price increases. These negative effects include unjust wealth distribution, malinvestment, stagnant growth and wages, runaway sovereign debt, and the eventual corrosion of public morality. The problem of inflation is far greater than a rise in consumer prices.

Second, government monetary authorities cause inflation and all its adverse effects by seizing control of the money creation decisions normally made by private commercial bankers and then directing that new money to groups who benefit unjustly. In 1980s Japan, they did it by commanding the commercial banks to lend wantonly to the property sector. In the USA, from 2009 to 2022, they did it by commanding the commercial banks to participate in massive purchases of government bonds, a program called “quantitative easing,” directing new money first to the Wall Street investor class and ultimately to Main Street consumers and businesses. Analysis of other asset bubbles reveals a similar path.

In closing, let’s give the last word on inflation to the great Henry Hazlitt:

“[Inflation] discourages all prudence and thrift. It encourages squandering, gambling, and reckless waste of all kinds. It often makes it more profitable to speculate than to produce. It tears apart the whole fabric of stable economic relationships. Its inexcusable injustices drive men toward desperate remedies. It plants the seeds of fascism and communism. It leads men to demand totalitarian controls. It ends invariably in bitter disillusion and collapse.” [vii]

Notes

[i] Seth Carpenter, Global Chief Economist at Morgan Stanley, “A Headwind for Policy Normalization: Morgan Stanley adds El Nino to List of Inflation Risks,” Zerohedge, September 10, 2023, https://www.zerohedge.com/markets/headwind-policy-normalization-morgan-stanley-adds-el-nino-list-inflation-risks.

[ii] Mises Institute, Transcript of remarks before the Conference on the Economics of Mobilization, held at White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia, April 6-8, 1951, under the sponsorship of the University of Chicago Law School. https://mises.org/library/economic-freedom-and-interventionism/html/p/123.

[iii] Reisman, Capitalism, Kindle Edition, 219. As I cannot do full justice to the topic of inflation in this essay, I recommend reading Chapter 7, which includes a thorough discussion of inflation, shortages, and price controls.

[v] “M2 for Japan.” FRED Economic data, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/MYAGM2JPM189S.

[vi] Despite its overvalued economy, Japan was able to invest overseas because the currency market (currency traders) did not devalue the Yen. According to Werner, they didn’t devalue because they did not see or understand the excess money creation. The same thing happened in the USA during the 1950s and 60s when US banks created excess dollars. US corporations used this plentiful, overvalued (“hot”) money to buy up European corporations.

[vii] Henry Hazlitt, Economics in One Lesson (Currency Books, 1979), Chapter 23, 176.