Michel Gibson was on the road to a career in the academic world. He was about to begin a Ph.D. program in philosophy at Oxford, when he realized that a professorship wouldn’t give him the freedom for deep, independent thinking and writing he longed for. He began to think deeply and independently about what has happened to American higher education and came to the radical conclusion that it’s a big waste of time, money, and talent. He blames it for the slowdown of innovation.

Plenty of people complain about our ineffectual education system, but Gibson is actually challenging it. He has created the 1517 Fund, which invests in young people who have ideas and ambition. Gibson helps them to get business ventures off the ground with startup financing—but the deal is that the recipients must either have dropped out of college or never enrolled at all.

You might be thinking, “Haven’t I heard of something like that before?” Yes, you probably have. Back in 2011, Peter Thiel began his Thiel Fellowship program. It sought young people who were willing to eschew college to get on with their ideas, giving them grants of $100,000 and access to Thiel’s business savvy. Not long after Gibson bailed out of academia, he took a job with Thiel, at first as an investment analyst, but soon to help get the Fellowship up and running.

After five years with the Thiel Fellowship, Gibson decided to strike out on his own, searching the world for talented young people to invest in. Gibson has now written an incendiary book entitled Paper Belt on Fire: How Renegade Investors Sparked a Revolt Against the University. It is a combination of a memoir recounting his time with the Thiel Fellowship and then his efforts at getting his own 1517 Fund going, and a manifesto setting forth Gibson’s indictment of our educational system, which has turned into a huge waste of time, money, and above all, talent.

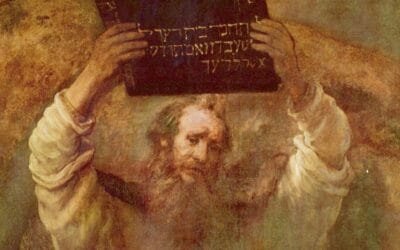

So, what is the 1517 Fund? It is Gibson’s way of finding young people who have ideas and want to put them into effect without the long, expensive detour through college. The name comes from the year when Martin Luther posted in 95 Theses, attacking the Catholic Church for its corrupt sale of indulgences to the faithful who believed they brought salvation. Gibson sees the modern university as doing essentially the same thing, selling expensive pieces of paper (degrees) that will supposedly bring the holder a life of success and fulfillment. They have grown astoundingly wealthy (dozens have endowments in excess of $1 billion and nine even have endowments of over $2 billion per student), yet they continue charging students huge sums to attend and, as the “Varsity Blues” scandal revealed, some will, in effect, sell admission to mediocre students as long as they’ll collect a big enough check from someone in the family.

The high cost of college degrees is bad enough, but Gibson is more concerned about the way schools fail to challenge the brightest students, wasting their time on courses they don’t want or need and “turning them into krill for too-big-to fail corporate leviathans.” He approvingly cites George Mason University economics professor Bryan Caplan, who argues in his book The Case Against Education that college degrees are no longer about acquiring useful skills and knowledge, but merely a means of signaling that the student is trainable. Instead of allowing sharp, energetic young men and women to vegetate in colleges, Gibson is on a mission to find them and put them on the fast track to success.

He is accomplishing his mission. The 1517 Fund has a growing portfolio of profitable companies started due to its support. Moreover, his idea is spreading; other funds are now doing the same thing, and on a few occasions, the 1517 Fund has suffered from the “cram down” when another fund poaches a rising star. Despite the hand-wringing from the education establishment that Thiel, Gibson, and others are doing something terrible when they persuade smart young people to eschew college. Their idea is catching on.

The world faces a lot of serious problems and, Gibson says, the rate of progress has “flatlined” for the last fifty years, but the mania for educational credentials keeps a lot of talent locked away for years on end. “Our education system,” he writes, “takes its sweet time pushing students out to the frontier in any subject, not because it’s difficult, but because there’s no urgency to get them there. The final, damning point is that the institutions simply don’t trust younger scientists and inventors. Grant-making bodies cover their asses by awarding research funding only to the established over the new, the prestigious over the experimental.”

What will happen to the US if we don’t break out of the college credential funk? We will gradually decline in prosperity and innovation, that’s what. Gibson points to economist Joel Mokyr’s book The Lever of Riches, where he argues that nations go into decline when they stop innovating and rest on their laurels, as was the case with China from the fourteenth century on. The same malaise is now affecting America. Gibson quotes former Google CEO Larry Page: “There are many, many exciting and important things you could do that you just can’t because they’re illegal or they’re not allowed by regulation.”

Indeed so. America has gone from a society where the people were free to try almost anything to one where they must seek permission from authorities—authorities who have little if anything to gain from saying “yes” and much to lose if they do. Regulators usually embrace the “precautionary principle” and drag their heels until they’re satisfied that no one will be harmed if an innovation is approved. (That problem is not the same as Gibson’s major complaint about the way our education system squanders talent, but they’re closely related and both need to be solved.)

Gibson is scornful of American university leaders. They constantly talk about how their schools “transform” students and enrich their lives, but never provide any actual evidence for those claims. Do students gain much in knowledge and skill from the day they first enter upon campus until the day they leave? Schools could test for that, but for some reason don’t.

A positive thing that our academic leaders could do would be to have their various departments set forth the top five unsolved problems in their respective fields, and free their faculty members to work on them. Gibson isn’t optimistic about the prospects of that happening, however.

What I have long called “the college bubble” has begun to deflate, as more and more young Americans realize that the costs exceed the benefits. So far, the schools suffering enrollment declines have been smaller, regional institutions; the prestige colleges and universities still have far more applicants than spaces. That attests to the strength of the belief that a degree from the likes of Harvard is worth the high cost in time and money. But that belief is apt to change as Gibson, Thiel, and others continue to help sharp and ambitious young people succeed just with their innate talents.