With Martha Stewart going on trial this week, it’s a perfect time to take a look at insider trading. From what I can tell, Ms. Stewart is being railroaded. And whatever the merits (or lack thereof) of the case against her, investors shouldn’t be especially worried about insider trading anyway. The odds that you are going to end up getting hurt trading against someone with material inside information are probably lower than the odds of being hit by lightning on the same day you win the lottery.

And there’s another kind of insider trading that you shouldn’t worry about, either. I’m talking about the billions of dollars in ordinary and perfectly legal buys and sells that corporate officers and directors make in their companies’ stocks every year.

Right now the media are trying to convince investors that insiders are bailing out of the market in record numbers. But as you’ll see, like so many media scare stories about the market and everything else, this one pretty much evaporates when you talk to the experts who really understand the numbers.

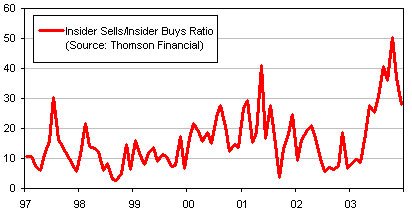

The chart below shows the kind of thing the media is trying to scare you with. It’s the ratio of the dollar value of insider sells to insider buys. As you can see, since the stock market started to recover from its major bottom last March, the insider sells have swamped insider buys by a record amount.

Does this mean that insiders are dumping stock into a rally that they don’t truly believe in? Fear not. As usual, the numbers are not what they seem.

Eric Bjorgen, a senior analyst at the Leuthold Group, told me that insider selling is not in record territory. He said, “We’ve seen a rise in selling, but nowhere near levels that pose a concern.”

So why is the ratio of sells-to-buys so steep? Bjorgen says, “It’s just because buying has dried up. That’s very typical of the early stages of a recovery. Insiders don’t really tend to buy the bottom as you might think.”

Another reason is that stock options mask the true amount of buying. In the past, an insider who wanted to buy his company’s stock had to do it in the open market and report the trade on SEC Form 4, the source of publicly available insider trading statistics. But nowadays many executives receive stock options as part of their total compensation packages. If they want to own stock, they exercise their options and buy the stock directly from the company — and the buy never gets reported.

But when they sell the stock purchased by options exercise, then they have to fill out Form 4 like everyone else. Lon Gerber, director of insider research at Thomson Financial, told me that options-related selling is now especially intense, thanks to the bull move that began last March. He says, “A lot of options issued in 2001 and 2002 that were underwater for a long time are finally in-the-money.”

Another insider trading statistic that’s getting a lot of play in the media is that the sheer number of insider sell trades is at an all-time high. That’s true, but Leuthold’s Bjorgen points out that this is only the result of a new SEC regulation that began in 2003. He says “a separate filing must be made for every different price, even if the transactions occur on the same day.”

So suppose a CEO exercises options he’s held for years, and acquires 100,000 shares of his company’s stock. He sells in 10 blocks of 10,000 each, at 25, 25.05, 25.10, and so on up to 25.45. The records would show zero insider buy trades that day, and 10 sell trades. And they’d show zero dollars worth of buys, but $2,522,500 worth of sells.

In Bjorgen’s work with these statistics, he tries to filter out all these effects. And he also likes to focus on big-block insider trades, because “big bets convey a level of conviction.” The bottom line according to Bjorgen? Insider trading is currently not bearish at all, but rather “within neutral territory.”

Now let’s stop and ask a fundamental question about all this. Whatever insiders may be doing, does it really matter? It seems to be an article of faith that insiders have the best information about their companies, so it would follow that their trades should be especially well timed. But is this really true?

Sure, if an insider knows that his company is about to strike oil or announce a cure for cancer, that information would make a heck of a buy. But with information that powerful, that buy would be illegal. So yes, insiders have valuable information. But it’s not that valuable.

And the proof is in a number of recent academic studies that show that, properly measured, the performance of insider buys and sells isn’t really all that much better than you could get yourself by following a few simple rules.

Dirk Jenter at the MIT Sloane School of Management has written a paper called “Market Timing and Managerial Portfolio Decisions.” Jenter finds that corporate executives, as a class, simply tend to act like classical contrarian investors. He told me, “They like all the categories that have traditionally outperformed the market: small stocks, high dividend stocks, and value stocks.”

According to Jenter, if over time you’d simply bought a diversified portfolio of small-cap stocks with high yields and low price/book ratios, you’d pretty much have gotten the same return as the group of insiders he studied. He told me, “It’s clear that managers know a little more, but it’s probably less than we thought in the past.” So who needs inside information?

Why don’t insiders do better? The reason is that unless you’ve got inside information as red hot as a new cure for cancer, it’s actually quite difficult to predict how a stock will perform when some particular piece of news is made public. Think about it. How many times have you bought a stock because you thought there would be a big upside earnings surprise, and it turned out that you were perfectly right — but the stock went down!

So, according to MIT’s Jenter, corporate executives tend to buy and sell their companies’ stock using the same kind of rules they would use to determine when to do share buybacks or issue new shares. In a nutshell, they make a simple judgment call on whether the stock was overvalued or undervalued — just like any contrarian investor would. And just like you could.

Interesting lesson, isn’t it? Once again, the media have trumped up a phony reason to scare investors into thinking the end of the world is just around the corner. But more important, here’s a case where investors have swallowed the myth of the infallibility of a class of elite market players — when, in fact, this so-called elite hasn’t really invested much smarter over time than you could do, if you just play it conservative and smart.

Remember, this game’s not so tough. You just have to be sure to get scared of the right things. And don’t let anyone tell you that you can’t beat this game.

The above is an “Ahead of the Curve” column published January 23, 2004 on SmartMoney.com, where Luskin is a Contributing Editor.