When President Bush first announced his plan last January to cut taxes on dividends, capital gains and personal income I sang his praises (first here, here and also here and here). Now Bush’s plan has been law for over two months. While the critics have had no shortage of things to hate about it, I’m still as enthusiastic as ever. And why not: The economy and the stock market are happier places since the tax cut went into effect.

Just look at the evidence: Markets that reflect growth are up, with stocks recovering more than 24% from March lows and high-yield bonds having just turned in a record run. On the other hand, markets that reflect fear and risk-aversion are in tatters, with Treasury bonds having fallen more over the last 10 weeks than almost at any other time in a decade.

Even the slow-moving government economic statistics are starting to look good again. Gross-domestic-product growth for the second quarter was surprisingly strong. Unemployment is easing. Consensus S&P 500 earnings grew this month at a better-than-20% annualized rate. Orders for durable goods are up. New-home sales hit an all-time record. Venture-capital investments showed the largest quarterly gain in three years. OK, there was a disappointing consumer-confidence report this week — but are you going to listen to what consumers are doing, or what they tell some pollster?

This is all exactly what happens when people are given an improved set of incentives to work, invest and take risks. In short, it’s what happens when taxes are cut.

There are subtler signs that the tax cuts are working, too. Public companies are beginning to respond powerfully to the changing tax treatment of dividends. These are even more encouraging to me because they imply long-term structural changes in economic behavior that will have major payoffs for years to come. Consider these facts:

- New equity issuance is sharply higher.

- There’ve been 719 dividend-increase announcements so far this year, compared with 550 at this point in 2002. The number of such announcements from June 1 through July 25 was 74% greater than during the same period last year. And 210 companies have announced a dividend increase since President Bush signed his tax cuts into law on May 28.

- More than 60% of the companies have hiked dividends by more than 10%. The average increase has been 28%. Some dividend increases have been enormous — Citigroup, for example, raised its dividend by 75%.

- Giants like Microsoft and Viacom are among the 134 nondividend-paying companies that started paying one this year.

Why is all of this so important? Because when the tax laws make it disadvantageous to pay dividends instead of interest, corporations do things that are tax-smart but growth-stupid. They issue debt instead of equity, which leaves them overleveraged in a downturn. And instead of paying out earnings to shareholders who might have better things to do with the money, corporate managers hoard it or — even worse — spend it on useless perks or uneconomic acquisitions.

There’s no doubt in my mind that cutting the tax on dividends will make the economy more efficient by eliminating these behavioral distortions. And there can be no doubt that a more efficient economy is a faster growing economy.

I know what you’re thinking: That’s all well and good, but what about those record budget deficits?

First of all, those deficits aren’t really at “record” levels. They may be the biggest dollar amount of deficits we’ve ever seen before, but the overall economy is much larger, too. As a fraction of the total economy, today’s deficits are lower than deficits both in the 1980s and the 1990s. I made much the same point in my column about deficits in April.

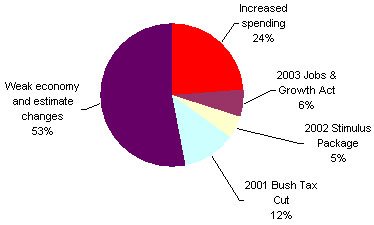

As the White House admits, while these deficits may be manageable, they’re still a concern. But for the most part, Bush’s tax cuts didn’t cause them — and the partisan critics who keep saying in the media that they did are simply wrong. According to a study released last week by the bipartisan Congressional Joint Economics Committee, the three tax cuts enacted under the Bush presidency have made only a small contribution to greater-than-forecasted deficits for fiscal 2003. Altogether, all three tax cuts are responsible for only 23% of the approximately $750 billion in increased deficits.

Factors behind the 2003 deficit growth

(April 2001 baseline vs. July 2003 estimate)

Source: Congressional Joint Economic Committee

While boosts to government spending explain slightly more of the increased deficit — 24% — the real culprit is the poor performance of the economy since January 2001. That’s responsible for 53% of the increase in the deficit, because in a slow economy tax receipts come in much less than expected. The same thing happened in the last two recessions.

How, you may ask, can a slow economy have such a dramatic effect? After all the economy has continued to grow at least somewhat, and unemployment hasn’t increased that much — so why have tax receipts fallen so dramatically? The answer is that a slowdown in economic growth hits high-income earners the hardest. Normal wage earners tend to keep their jobs, but people like salesmen or executives who’d been highly compensated by commissions or stock options find their incomes dramatically reduced. And they’re the ones who pay the highest tax rates on their income.

This is why I just laugh when I hear some partisan economists warn that we can’t afford tax cuts because tax cuts lead to deficits, and deficits lead to slow economic growth. The reality is that it’s the other way around. It’s slow growth that causes deficits — and the best way to stimulate faster growth is to cut taxes.*

So I agree with the administration’s economists who argue that these high deficits are manageable and temporary. The reinvigoration of economic growth that we’re just beginning to see now will cure the deficits as quickly as economic stagnation caused them.

But that’s only a side-effect. Remember: Economic growth is an end in itself. Sure, it’ll take care of America’s deficits. But more importantly, economic growth creates more opportunities for all American’s to reach their highest levels of personal achievement and to enjoy a higher standard of living. And isn’t that what we’re all here for?

*Publisher’s Note: This is true in part–government deficits are because government is spending more money then it receives. The key to preventing deficits is simply for the government to stop spending more than it takes in from taxes. Economic growth helps reduce deficits since growth (income) is taxed, so that the greater the income the greater the taxes. See this news item for a contrasting view.