Hard boiled detectives often live in a brutal world. Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, and above all, Mickey Spillane, did not write cozy mysteries of an Agatha Christie type. Victims often get their skulls bashed in or are riddled with .45 dum-dums. Other than lurid violence and sometimes combustible sex, what is the appeal of these stories?

To answer this question, let’s start with an example. In the 1950s and 1960s, Mickey Spillane’s novels about hard-boiled detective Mike Hammer were wildly popular; they sold many millions of copies and spun off several TV shows and movies. The stories often embroiled Mike Hammer in violent encounters from start to finish. Take, for example, the opening line from Vengeance is Mine: “The guy was dead as hell.” Mickey Spillane was a skillful writer who plotted well and knew how to draw the reader in. Consider the next sentence from that opening paragraph: “He lay on the floor in his pajamas with his brains scattered all over the rug and my gun was in his hand.” The reader is immediately intrigued. He has questions: How did the guy get dead as hell? Who got the guy dead as hell? Why is Mike’s gun in his hand? Did Mike kill him? Turns out the guy was an old World War II buddy of Mike’s. And then, Mike and the reader are off on a bloody trail of detecting, fighting, shooting, and a quest for violent justice.

Mike Hammer is a crusader for justice. Of central importance to the theme of this essay is that he is often a solitary crusader for justice. Pat Chambers is an honest NYPD Homicide cop and a friend of Mike’s but rarely teams with him in an investigation. Velda is Mike’s secretary who sometimes assists him in his cases. The two are genuinely in love—but while he has sex with random women he meets in the course of his cases, he never makes love to the woman he loves. Most of the time, he’s alone. He tracks down cold-blooded killers, he slugs it out with thugs, he often takes a beating and more often dishes one out; in the end, he discovers the murderer and generally kills him (or her) himself. He is a one-man battalion of bristling, two-fisted, remorseless justice. He is a 20th century example of what past American writers admiringly called “rugged individualism.”

Individualism is the moral code recognizing that a human being is first, foremost, and always an autonomous being, a bodily and spiritual individual, not a nameless, faceless, fungible, easily replicable member of a tribe or collective. He (or she) is unique and unrepeatable. Individualism is the code upholding the moral principle that a person’s life belongs to him or her, not to the state or to society; and that he possesses sovereign control of his own life. A man has the inalienable right to deploy his mind in service of his own life—and he has no unchosen obligation to sacrifice it for anything or anybody. His decision to help others or not is a personal choice, not a duty imposed by God or the state.

The phrase “rugged individualism” denotes the man of such indomitable independence that he can survive , even flourish and triumph, by his own devices under even the most arduous and/or dangerous circumstances. And, as Ayn Rand taught us, such an individual of invincible self-sufficiency has no need of victims. He may choose to protect the innocent from criminal parasites who prey on them—but he never victimizes them.

Justice is a paramount concern of the tough-guy hero. He has no need of victims and he will not tolerate victimizers. He hunts down murderers and other predators on innocent persons without remorse. In some form, he ensures they get what they deserve—whether he kills them, beats them to a bloody pulp, or turns them over with evidence to law enforcement, he avenges the victim(s) and protects future prospective ones. Jack Reacher is a perfect present-day example of such a hero. Sixty years ago, Mike Hammer was that guy. So are other tough-guy private detectives. Dashiell Hammett’s Sam Spade, Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe, John MacDonald’s Travis McGee, and others are cut from the same cloth.

Clearly independence is a major virtue of the hardboiled detective. Observe that even when he operates with a partner or a team, he is the expert regarding criminal justice, he goes by his own judgment, and others take their cue from him. This is a salient feature of my Tony Just novels. As I add Tony to the pantheon of tough-guy detectives, it is important to note that he sometimes investigates alone—but that he often works with a team.

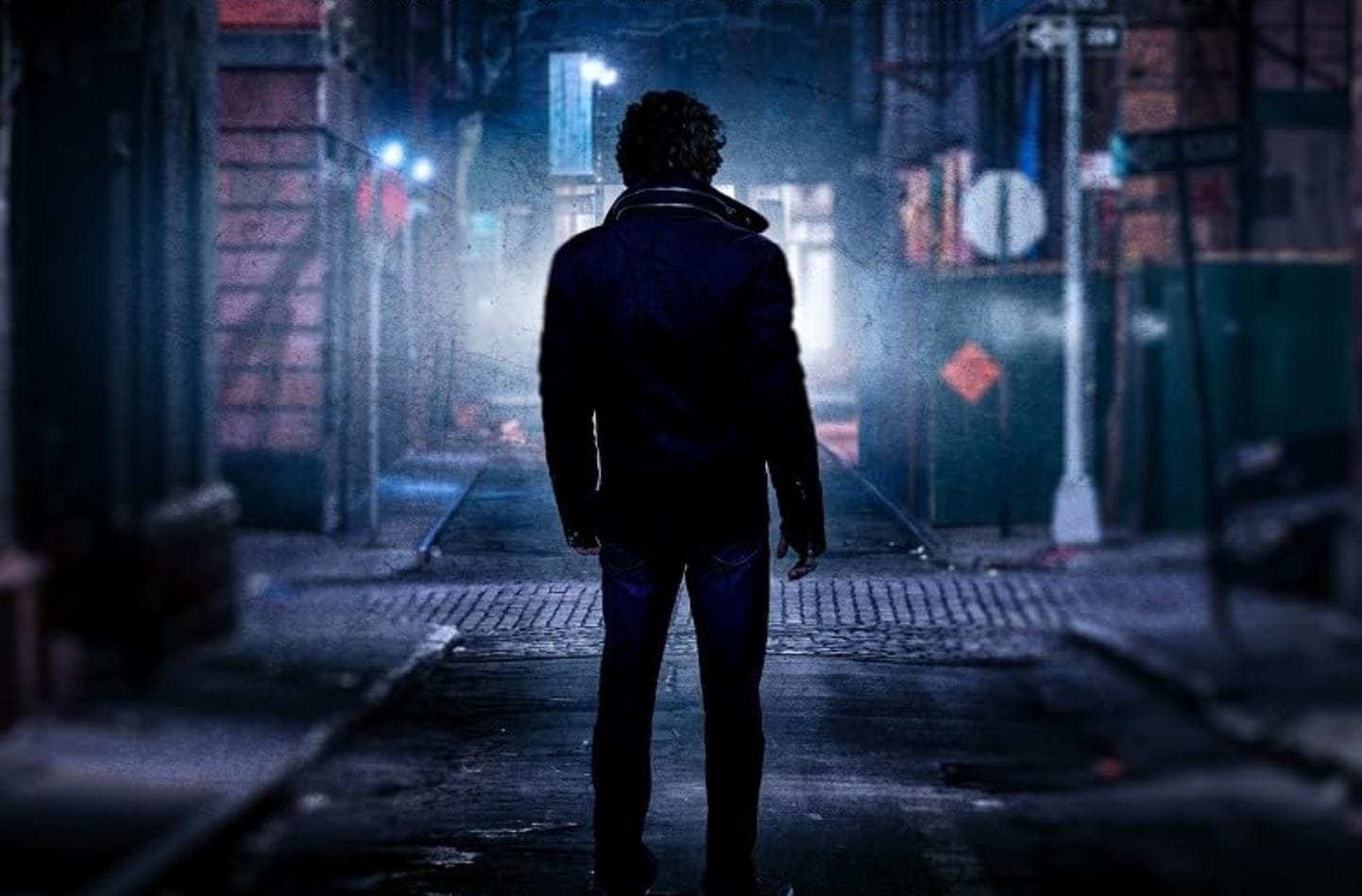

Tony’s real name is Anthony Justice. He is a former U.S. Army Intelligence officer who served two tours of combat duty in Iraq. He is a Philosophy professor at Brooklyn University by day and a part-time private eye by night. At some point, he may have to choose between professing and detecting but for now his nights are spent on Brooklyn’s meanest streets and his days in the university’s brightest classrooms.

Reggie H.A.R.D. is Tony’s partner. His keeps his real name private but fights professionally under the colorful stage name. He is a certified badass but he is also much more. He loves to read, he was abused as a bookworm as a child both at home and in the street, he took beatings and dished them out, he never relinquished his love of reading, and he is the most brilliant individual in the Tony Just universe. Nevertheless, in the field of criminal investigation, Tony is the go-to guy.

Lisa Flowers is the love of Tony’s life. She is a brilliant psychotherapist, she is married, she has a gangster past, she is expert with a handgun, and Tony realizes that she may or may not be trustworthy. Can he trust her? is a major question of Red Meat Village, Volume One of the Tony Just saga. But even Lisa at her best, with her deep intelligence and extensive education, defers to Tony when it comes to investigating crime.

Here lies the essence of the autonomous hero, especially of the tough guy variety: His judgment is the term setter of the goal pursuit—whether solving a crime or another—and other good guys follow his lead. Related and central to the popularity of hardboiled detectives is this: He often must make snap decisions under intense pressure with innocent lives hanging in the balance—and he damn well better get it right…or it will be the last decision he ever makes. In the universe of Red Meat Village and subsequent novels of the series, Tony Just is that guy.

Hardboiled detectives are independent men, they stand up to villains of every variety, they sometimes face opposition from the cops, they make the tough calls, they do it under life-and-death pressure, they face the consequences, they often bend the rules of legality, but they are always committed to justice. The tough guy detective may be aided or hindered by the official police force but he goes his way regardless, doing what he knows is tight and pursuing justice. As readers will see, Tony Just is a prime example: He has a tortured relationship with NYPD Homicide cop, Detective L.T. Coombes. Tony has broken so many laws in the course of his exploits in Red Meat Village that Detective Coombes is determined to prosecute him for obstruction of justice. But nothing—not the cops, not the drug cartel, not vicious hit men hot on his trail—prevent Tony Just from doing the right thing as he understands it.

The sight of such a hero, a rugged individualist dedicated to bringing justice come what may, is inspiring; and the popularity of these tough guy detectives shows that many Americans still value the individualism of the country’s heritage.