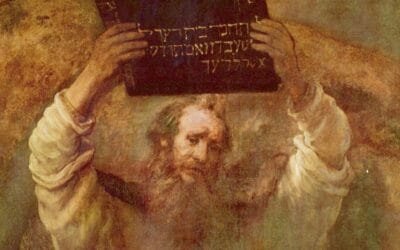

On March 2 the US Supreme Court will hear oral arguments to decide whether monuments presenting the Ten Commandments on government property constitute an establishment of religion in violation of the First Amendment.

But even as we get caught up in the familiar legal-constitutional debates, there is a much deeper set of issues that finds no forum and no discussion: What are the Ten Commandments? What is their philosophic meaning and what kind of society do they imply?

Religious conservatives claim that the Ten Commandments supplied the moral grounding for the establishment of America. But is that even possible? Let’s put aside the historical question of what sources the Founding Fathers, mostly Deists, drew upon. The deeper question is: can a nation of freedom, individualism and the pursuit of happiness be based on the Ten Commandments?

Let’s look at the commandments. The wording differs among the Catholic, Protestant and Hebrew versions, but the content is the same.

The first commandment is: “I am the Lord thy God.”

As first, it is the fundamental. Its point is the assertion that the individual is not an independent being with a right to live his own life but the vassal of an invisible Lord. It says, in effect, “I own you; you must obey me.”

Could America be based on this? Is such a servile idea even consistent with what America represents: the land of the free, independent, sovereign individual who exists for his own sake? The question is rhetorical.

The second commandment is an elaboration of the above, with material about not serving any other god and not worshipping “graven images” (idols). The Hebrew and Protestant versions threaten heretics with reprisals against their descendants–inherited sin–“visiting the iniquity of the fathers upon the children unto the third and fourth generation . . .”

This primitive conception of law and morality flatly contradicts American values. Inherited guilt is an impossible and degrading concept. How can you be guilty for something you didn’t do? In philosophic terms, it represents the doctrine of determinism, the idea that your choices count for nothing, that factors beyond your control govern your “destiny.” This is the denial of free will and therefore of self-responsibility.

The nation of the self-made man cannot be squared with the ugly notion that you are to be punished for the “sin” of your great-grandfather.

The numbering differs among the various versions, but the next two or three commandments proscribe taking the Lord’s name “in vain” and spending a special day, the Sabbath, in propitiating Him.

In sum, the first set of commandments orders you to bow, fawn, grovel and obey. This is impossible to reconcile with the American concept of a self-reliant, self-owning individual.

The middle commandment, “Honor thy father and mother,” is manifestly unjust. Justice demands that you honor those who deserve honor, who have earned it by their choices and actions. Your particular father and mother may or may not deserve your honor–that is for you to judge on the basis of how they have treated you and of a rational evaluation of their moral character.

To demand that Stalin’s daughter honor Stalin is not only obscene, but also demonstrates the demand for mindlessness implicit in the first set of commandments. You are commanded not to think or judge, but to jettison your reason and simply obey.

The second set of commandments is unobjectionable but is common to virtually every organized society–the commandments against murder, theft, perjury and the like. But what is objectionable is the notion that there is no rational, earthly basis for refraining from criminal behavior, that it is only the not-to-be-questioned decree of a supernatural Punisher that makes acts like theft and murder wrong.

The basic philosophy of the Ten Commandments is the polar opposite of the philosophy underlying the American ideal of a free society. Freedom requires:

— a metaphysics of the natural, not the supernatural; of free will, not determinism; of the primary reality of the individual, not the tribe or the family;

— an epistemology of individual thought, applying strict logic, based on individual perception of reality, not obedience and dogma;

— an ethics of rational self-interest, to achieve chosen values, for the purpose of individual happiness on this earth, not fearful, dutiful appeasement of “a jealous God” who issues “commandments.”

Rather than the Ten Commandments, the actual grounding for American values is that captured by Ayn Rand in Atlas Shrugged:

“If I were to speak your kind of language, I would say that man’s only moral commandment is: Thou shalt think. But a ‘moral commandment’ is a contradiction in terms. The moral is the chosen, not the forced; the understood, not the obeyed. The moral is the rational, and reason accepts no commandments.”

Copyright Ayn Rand Institute. All rights reserved. That the Ayn Rand Institute (ARI) has granted permission to Capitalism Magazine to republish this article, does not mean ARI necessarily endorses or agrees with the other content on this website.